Tissue Homogeneity

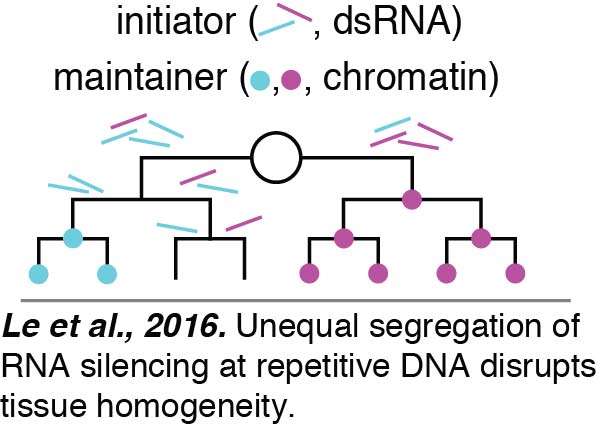

Through our studies on RNA silencing of repetitive DNA, we have stumbled upon a fundamental question that has received little attention: given the numerous components of a cell, how do animals keep any two cells similar within a tissue? We discovered that inhibitors of RNA silencing that are inherited from parents as well as made in developing progeny act in the embryo to eliminate variation between cells. In the absence of such factors, an initiator of gene silencing, likely dsRNA, is segregated unequally between cells during proliferative cell divisions required to make a tissue. This initiator causes threshold-dependent gene silencing. Consistent with the initiator being dsRNA, fewer cells show silencing when SID-1 is removed to block the spread of dsRNA between cells. Once initiated, the silencing is maintained by chromatin-mediated mechanisms despite DNA replication and cell division (Le et al., 2016).

Once different tissues have been specified through unequal cell divisions and signaling in the early embryo, subsequent cell divisions within a tissue could have to generate similar cells. Given the fundamental nature of this requirement, we suspect that many more processes in cells are under similar control to ensure a clean switch from differentiation to epigenetic memory during proliferative cell divisions that generate a tissue. Loss of such developmental mechanisms could potentially cause diseases later in life because of the generation of a variable population of cells within a tissue. This consideration is particularly relevant for age-related disease such as cancer that strike single cells apparently at random.

Understanding how such developmental mechanisms maintain the expression state of a gene will be essential to control the precise expression or silencing of a gene in every generation.

In the absence of such factors, an initiator of gene silencing, likely dsRNA, is segregated unequally between cells during proliferative cell divisions required to make a tissue. This initiator causes threshold-dependent gene silencing. Consistent with the initiator being dsRNA, fewer cells show silencing when SID-1 is removed to block the spread of dsRNA between cells. Once initiated, the silencing is maintained by chromatin-mediated mechanisms despite DNA replication and cell division (Le et al., 2016).

Once different tissues have been specified through unequal cell divisions and signaling in the early embryo, subsequent cell divisions within a tissue could have to generate similar cells. Given the fundamental nature of this requirement, we suspect that many more processes in cells are under similar control to ensure a clean switch from differentiation to epigenetic memory during proliferative cell divisions that generate a tissue. Loss of such developmental mechanisms could potentially cause diseases later in life because of the generation of a variable population of cells within a tissue. This consideration is particularly relevant for age-related disease such as cancer that strike single cells apparently at random.

Understanding how such developmental mechanisms maintain the expression state of a gene will be essential to control the precise expression or silencing of a gene in every generation.

Back to research

Last updated: Aug 2017

Web Accessibility